Giant cell tumor of tendon sheath, or pigmented villonodular synovitis, is an occasionally visible benign soft tissue tumor. It occurs mostly in the knee and can be divided into two types- solitary or diffuse. Diffuse type of pigmented villonodular synovitis is generally difficult to deal with, and it often cannot be completely cleaned up by surgery and will leave sequela with different symptoms. In addition, although this tumor has the word ‘giant cell tumor’ in its name, its clinical performance is completely different from the ‘giant cell tumor’ in the osteosarcoma category

Chinese: 腱鞘巨細胞瘤(the new name)、色素絨毛結節性滑膜炎(the old name be still widely used)

English: Tenosynovial Giant Cell Tumor, Giant cell tumor of tendon sheath、Pigmented villonodular synovitis、Benign synovial histiocytoma

The most common symptom of a giant cell tumor of tendon sheath (Pigmented villonodular synovitis) is joint effusion with pain. Often patients experience such a symptom for several years without finding a cause, and they eventually diagnosed the disease MRI scanning. The most typical clinical finding is that physicians can extract black-red blood-like joint fluid from the patient's knee.

Giant cell tumor of tendon sheath (Pigmented villonodular synovitis) is more common outside of the joint cavity, with ten cases out of a million people. Inner-joint cavity GCTTSs are rare, with only two out of a million people. Our outpatient clinic would affirmatively diagnose nearly 5 new patients in about a year at the Therapeutical and Research Center of Musculoskeletal Tumor in Taipei Veterans General Hospital.

Giant cell tumor of tendon sheath (Pigmented villonodular synovitis) occurs mostly in the young adult period, and the average age is about 35 years old. The ratio is similar for both genders but slightly higher for women.

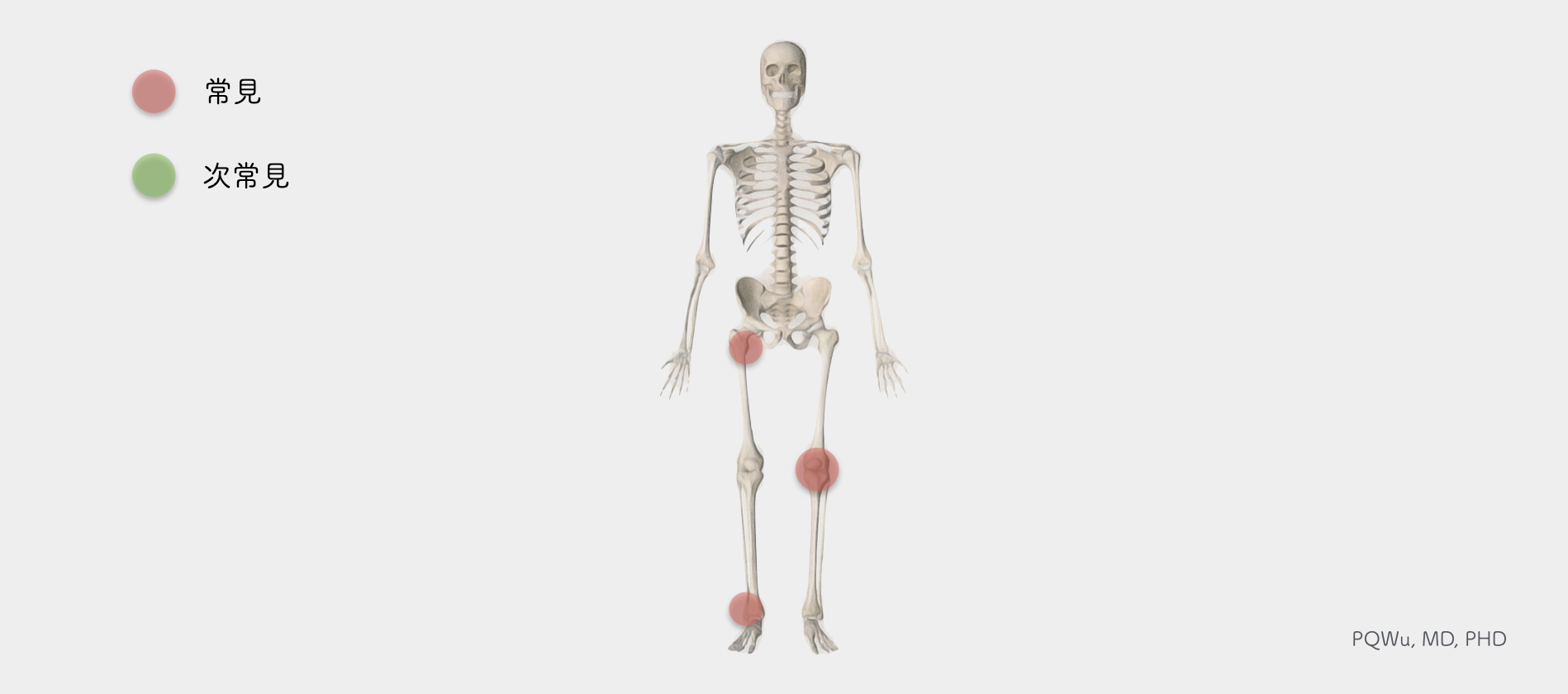

Giant cell tumor of tendon sheath (Pigmented villonodular synovitis) most commonly occurs in the knee joint, accounting for about 50%. Other common locations include the hip joint (about 20%) and ankle joint (10%), and a small amount of the tumor occurs in the temporomandibular joint, TMJ, and the spine. Basically, it happens only in one joint, not multiple at the same time.

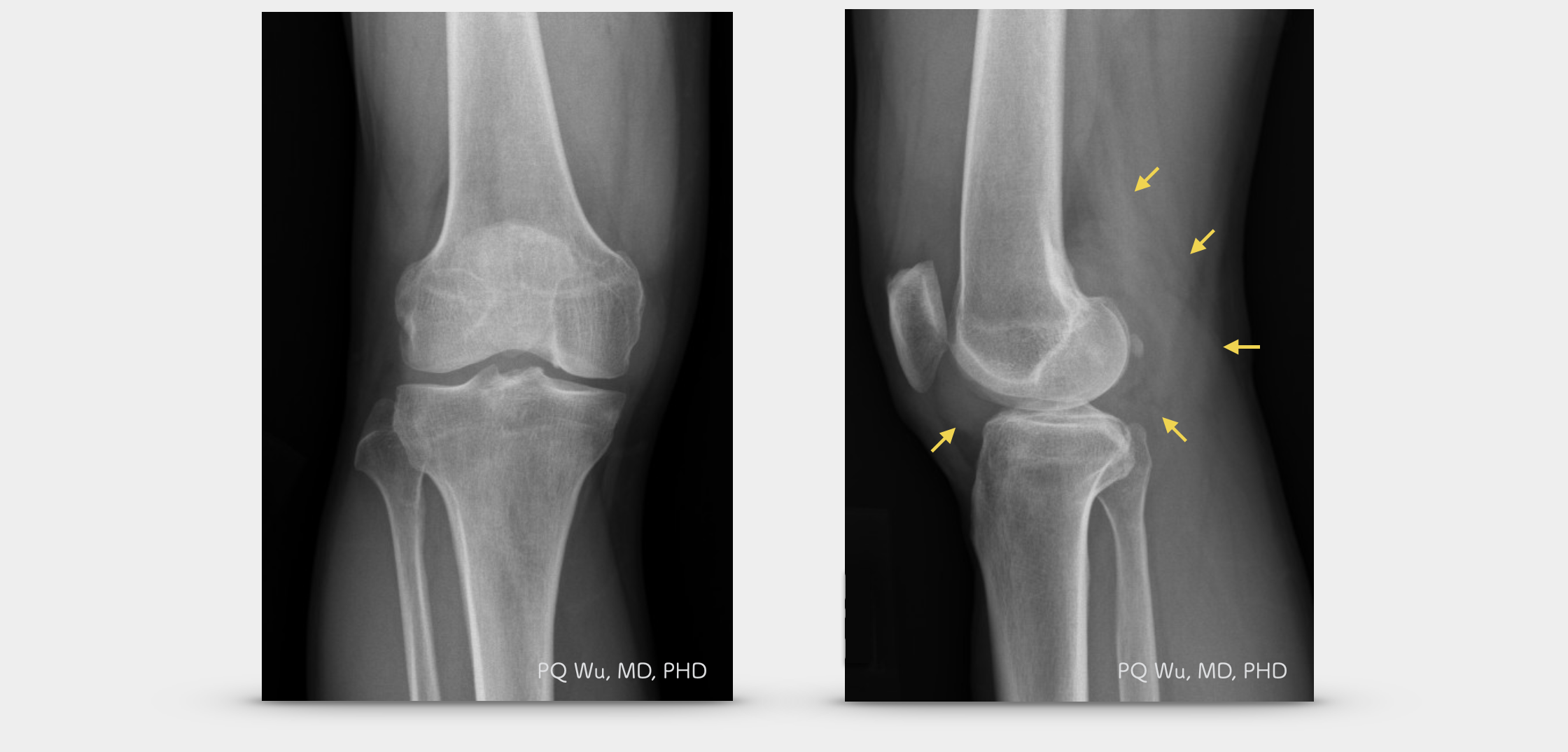

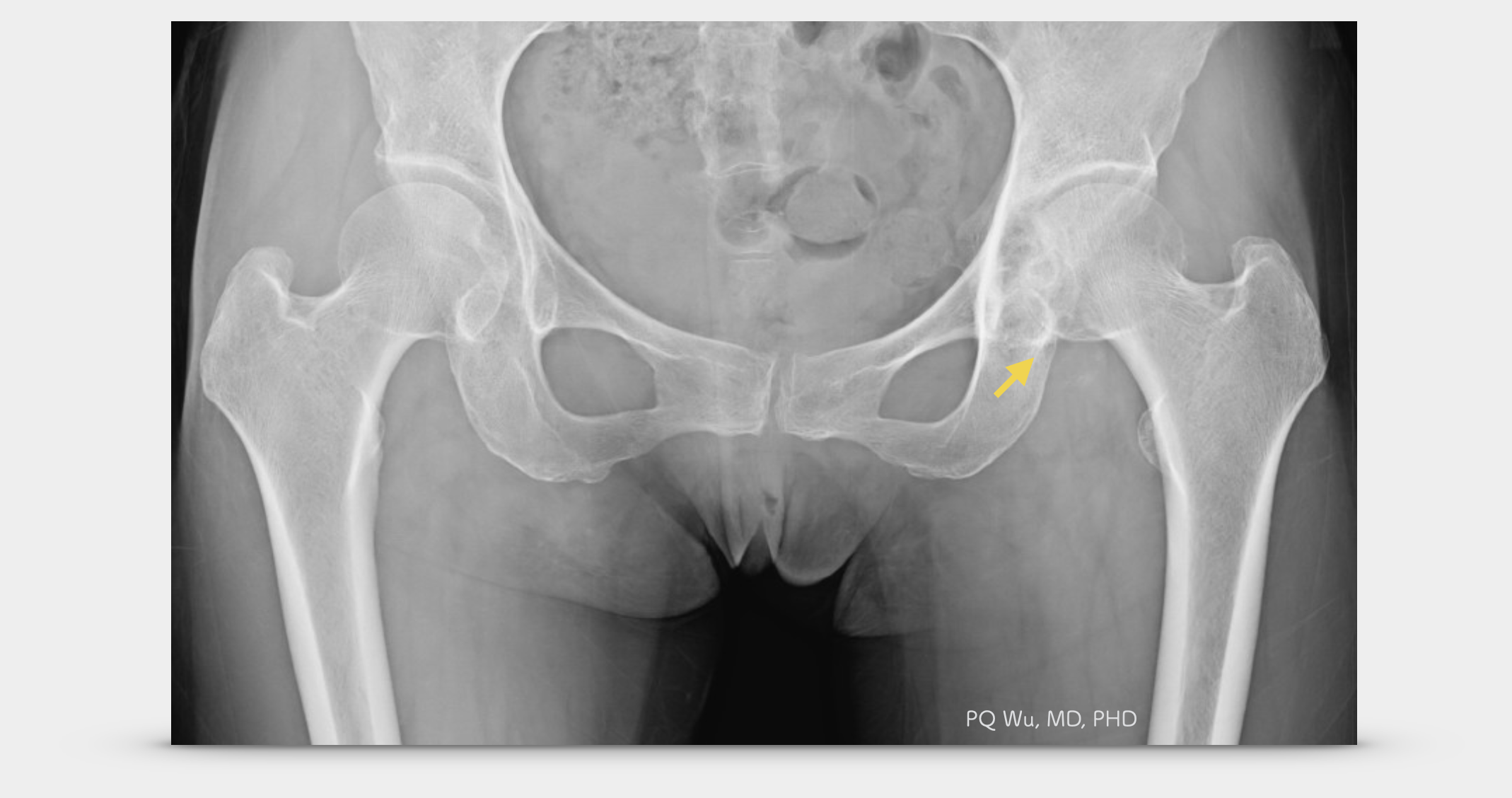

In X-ray images, the swelling of soft tissue can be seen in the GCTTS at the knee joint, and the destruction of bone tissue is less likely seen. However, if GCTTS occurs near the hip, it’s common to see the combination of bone destruction, and sometimes it is not easy to distinguish from avascular necrosis of the femoral head, AVNFH.

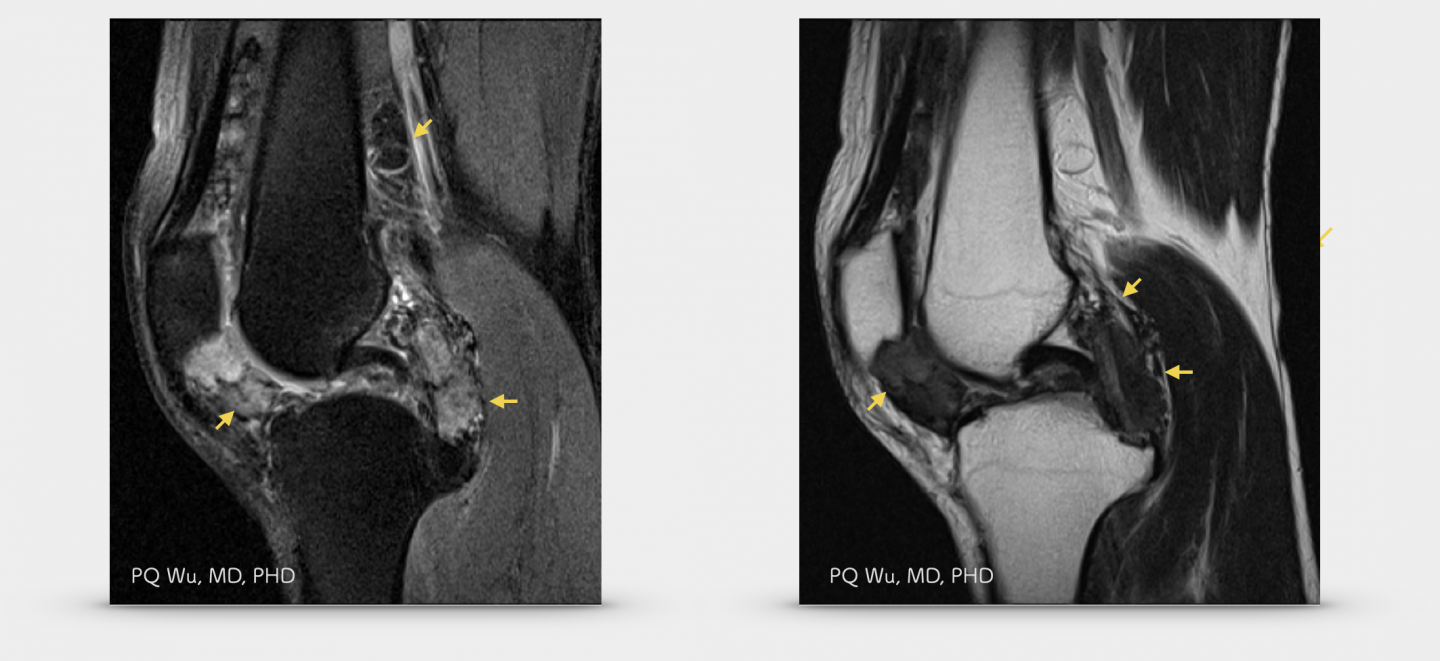

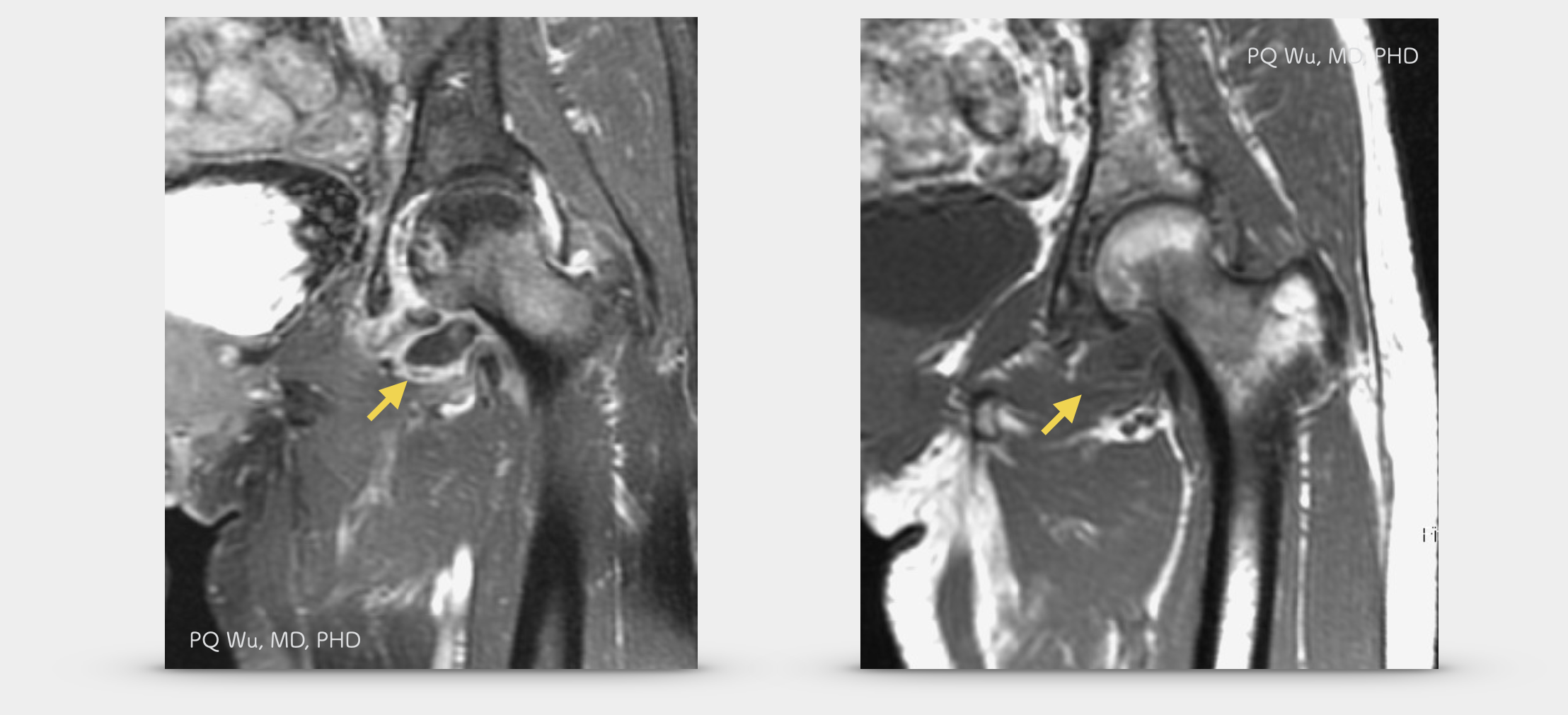

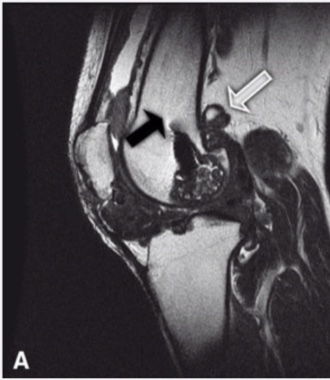

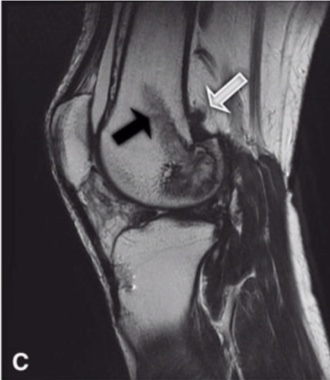

Under the MRI image, GCTTS has the most significant feature of special low T1 and T2 signals since it has abundant hemosiderin. This feature is an important indicator to distinguish GCTTS from other benign or malignant tumors. The following are the imaging performance of a 46-year-old male with knee GCTTS and a 58-year-old female with hip GCTTS:

A 46-year-old male with GCTTS at the right knee (X-ray)

A 46-year-old male with GCTTS at the right knee (MRI)

A 58-year-old woman with GCTTS at the left hip (X-ray)

A 58-year-old woman with GCTTS at the left hip (MRI)

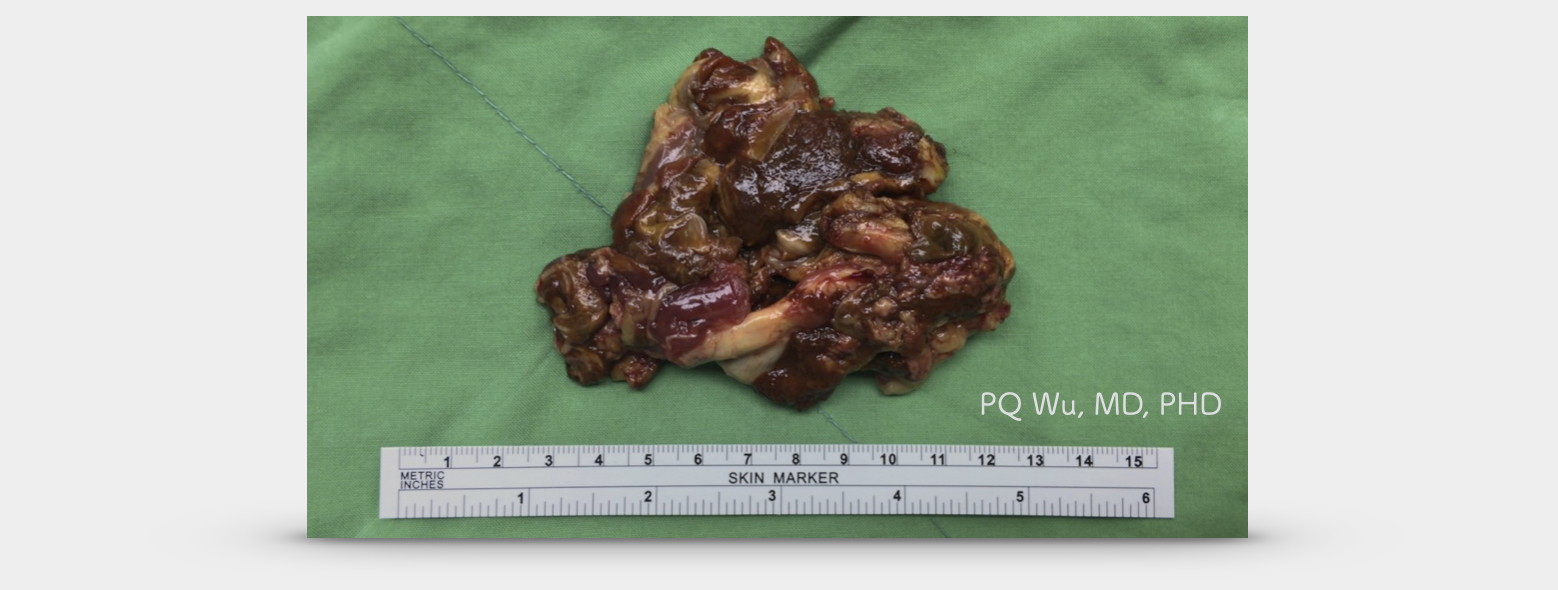

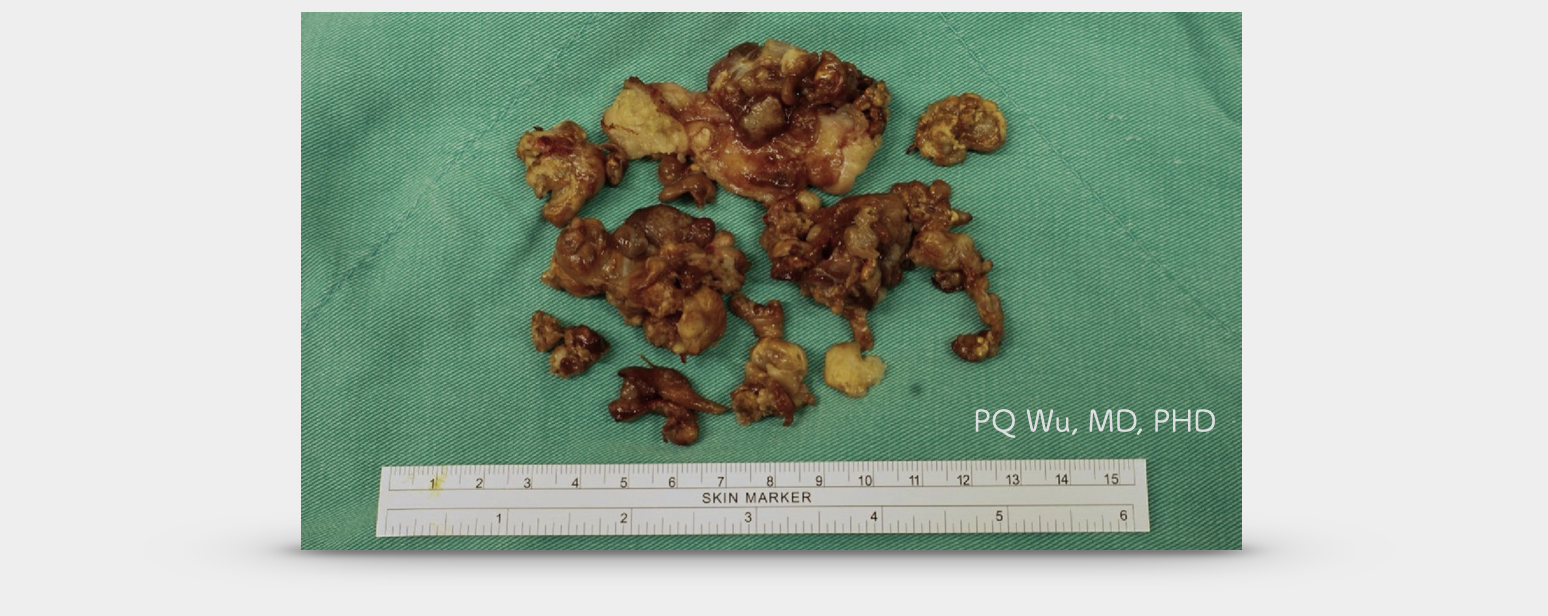

GCTTS has a fiber pattern with blood and coffee color, and it’s palpably solid at some places and soft at rest.

A 30-year-old female with pigmented villonodular synovitis at the right knee

A 38-year-old male with pigmented villonodular synovitis at the right knee

Under the microscope, we can see many synovial structures with the feature of villosity, papillae, and nodularity. So, it used to be called pigmented villonodular synovitis. Among them are mononuclear cells, osteoclast-like giant cells, and hemosiderin-rich cells that are characteristics of giant cell tumors

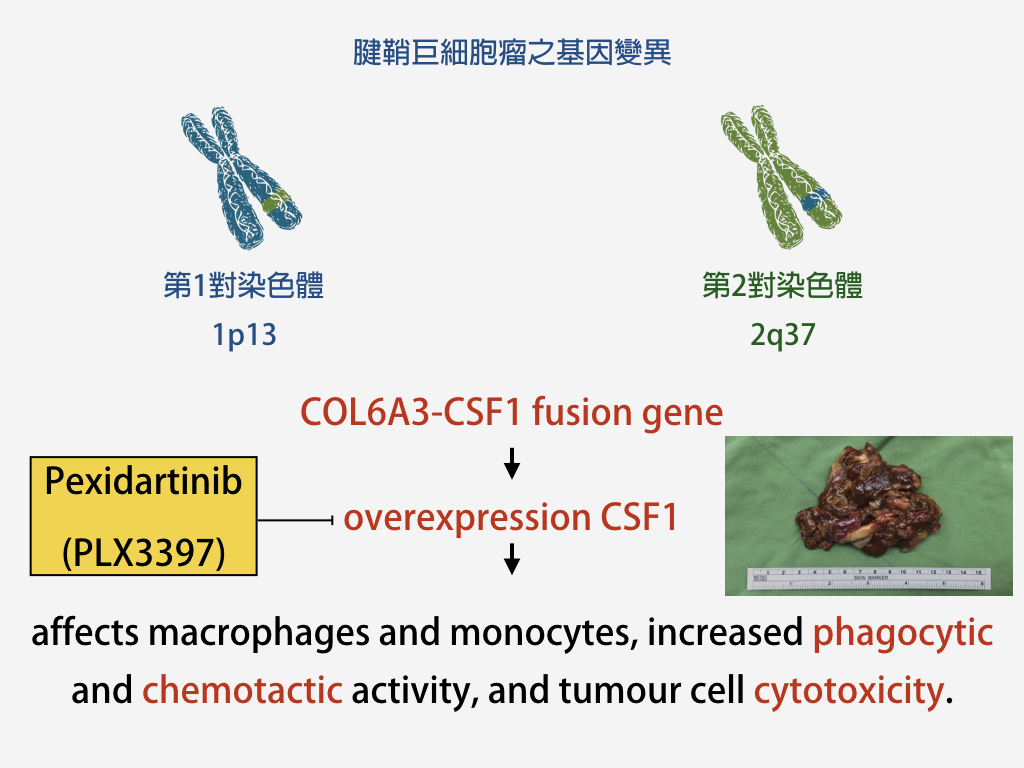

The cause of a giant cell tumor of tendon sheath, or pigmented villonodular synovitis, is not fully understood. Many studies have suggested that it may be associated with chronic inflammation, injury, and abnormal fat metabolism. In 2007 and 2008, two studies from the Stanford University in the United States(*) and Lund University in Sweden (**) reported the association between GCTTS and two mutations on the COL6A3 and CSF1 genes. Yet, in current studies, only about 20 percent of GCTTS formation is related to both genes.

* Translocation and expression of CSF1 in pigmented villonodular synovitis, tenosynovial giant cell tumor, rheumatoid arthritis and other reactive synovitides. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007 Jun;31(6):970-6.

**Molecular identification of COL6A3-CSF1 fusion transcripts in tenosynovial giant cell tumors.Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2008 Jan;47(1):21-5

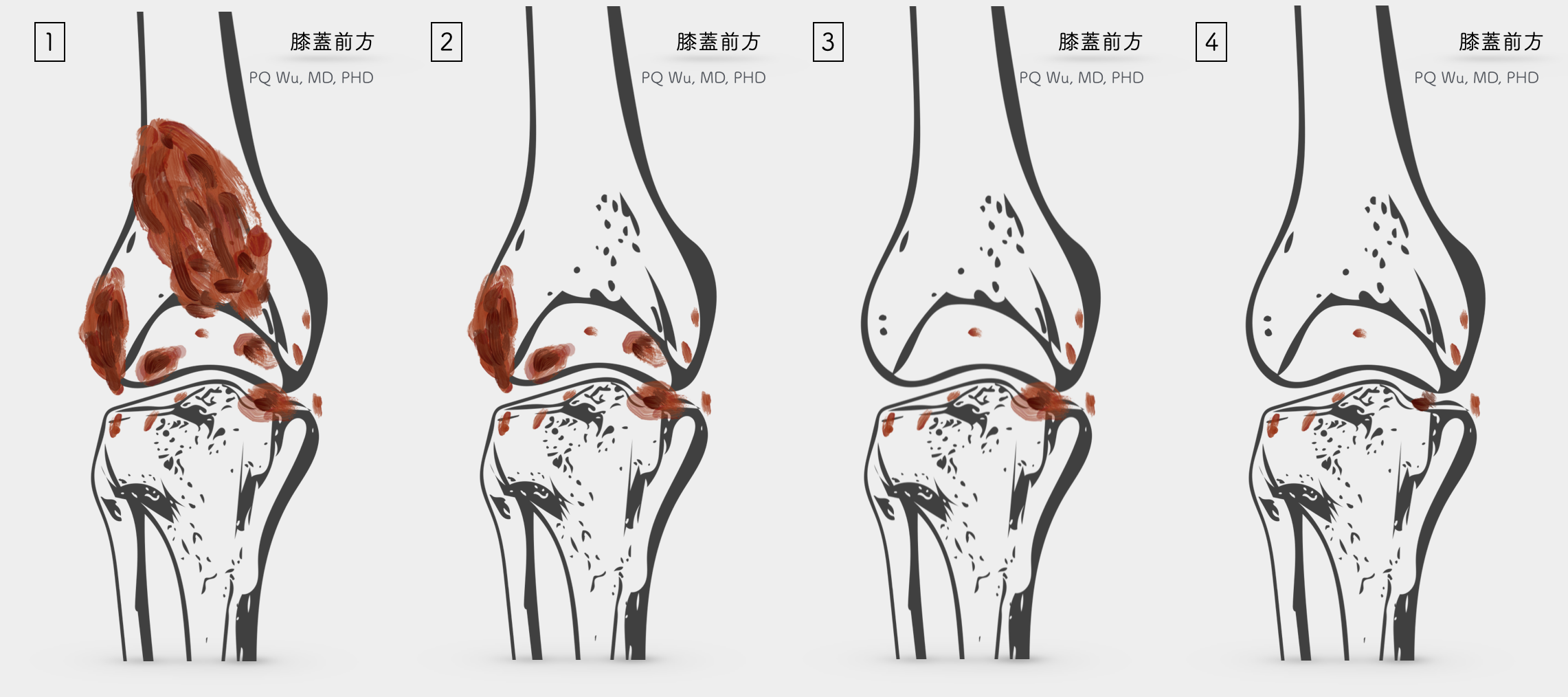

The classification of giant cell tumor of tendon sheath (pigmented villonodular synovitis) can be divided into two broad categories:

1. Solitary GCTTS- Most solitary GCTTSs occur outside the joint cavity, such as tendons in the hands. The treatment is relatively easy, and surgery can remove the tumor completely.

2. Diffuse GCTTS- Most GCTTSs that grow inside the joint cavities are diffuse types. Diffuse GCTTSs grow diffusively in the joint cavities and adhere to important ligaments, cartilages, and tendons. The treatment is difficult, and often surgeries cannot remove the tumor completely. So, the chances of having residual tumors and tumor recurrence after surgery are quite high.

In fairly rare cases, pigmented villonodular synovitis would turn malignant. Only one case has been seen in our past experience in the Therapeutical and Research Center of Musculoskeletal Tumor at Taipei Veterans General Hospital. It’s even rarely reported in medical journals.

The most important treatment for giant cell tumor of tendon sheath (pigmented villonodular synovitis) is 'surgery'. However, since the diffuse GCTTS will spread throughout the joint cavity and invade the entire bursa and cartilage, it is quite difficult to remove the tumor completely. Even the whole tumor is removed, the removal process destroys too many normal structures, causing serious damage to joint function and leading to very early degenerative arthritis.

Therefore, for such diseases, combinative approaches are usually adopted in most practices internationally. Doctors would perform the first surgery to remove the tumor at the front of the knee in the past. After two weeks of plaster fixation, a second surgery was performed to remove the tumor from the back of the knee. Then, six weeks after surgery, localized low-dose radiation therapy was given to reduce the chance of tumor recurrence.

In the Therapeutical and Research Center of Musculoskeletal Tumor in Taipei Veterans General Hospital, we modified this traditional way by combining the first and second surgeries without a post-surgical plaster fixation. Instead, we instructed patients to start active rehabilitation exercises the day after surgery. According to our study, this method can lead to better postoperative functional recovery. The result has been published in the well-known orthopedic journal- Clinical Orthopedics and Related Research, CORR, in 2012 (*). It is now the standard practice for the treatment of diffuse GCTTS worldwide.

A 34-year-old male, who received reconstruction at his anterior cruciate ligament, suffered continuous swelling—diagnosed with GCTTS at the knee.

Residual tumors can be observed three months after surgery and radiation therapy.

Nine months after surgery and radiation therapy, a significant reduction of the tumor was observed.

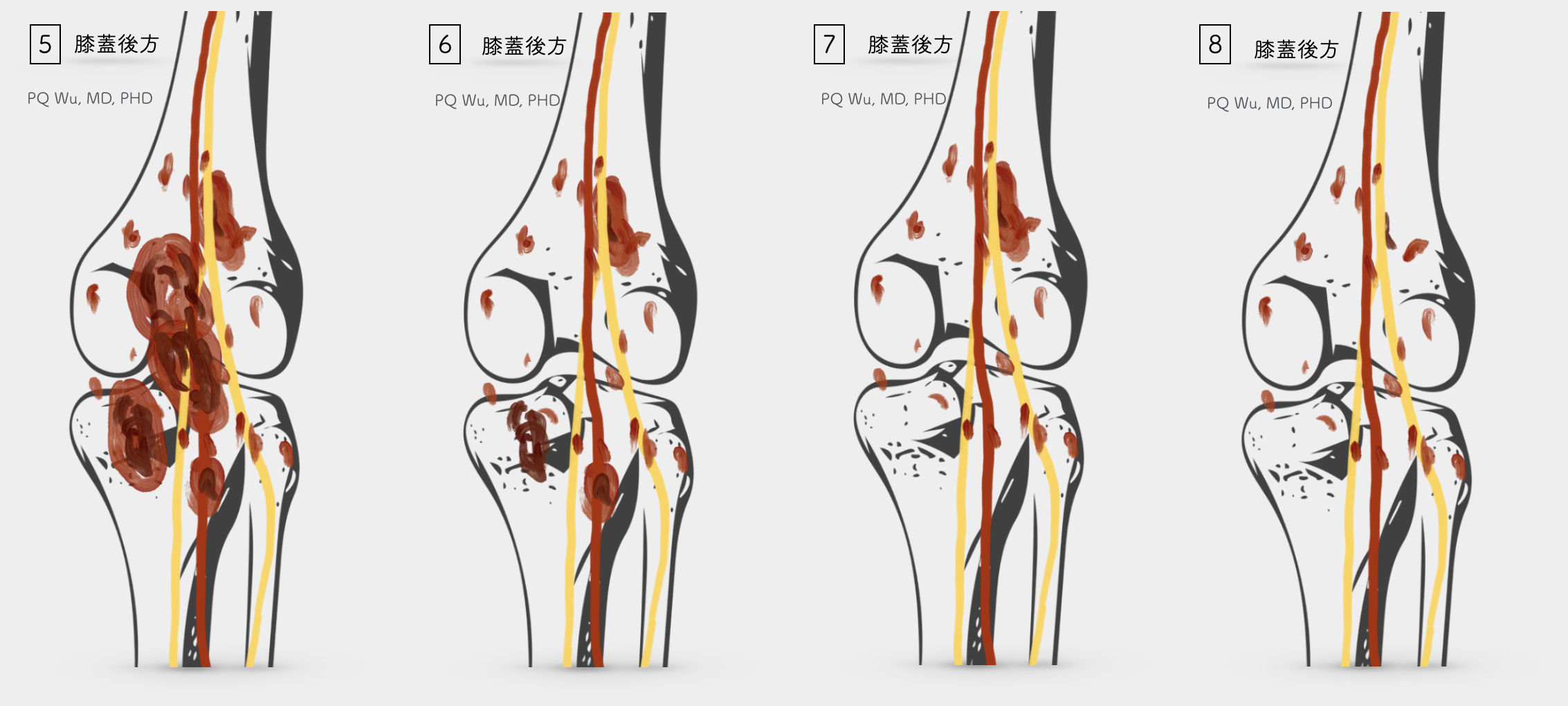

(5) Tumors behind the knee often adhere to nerve and vessels (5) then remove as much as possible of the tumor outside the joint cavity (7) Open the rear joint cavity and remove the tumor from the joint (8) Residual tumors that stick to the joint cavity and on the nerve and blood vascular wall

After surgery for diffuse GCTTS, the chances of 'residual' or 'recurrence' are quite high. According to medical reports overseas, it is as high as 14 to 56%. There are three reasons why there is such a high chance of recurrence:

1. The way the tumor grows is quite diffusive. It mostly spreads everywhere, and thus it’s quite difficult to completely remove it.

2. Tumors will adhere to cartilage, ligaments, nerves, and blood vessels. So, if removed completely, a serious effect on the patient's limb function will occur.

3. Tumors grow from the bursa, and if all the bursae are surgically removed, it causes severe degenerative arthritis afterward.

Therefore, to reduce the chance of post-surgical recurrence, the current global consensus is to give patients low doses of radiation therapy about four to six weeks after surgery. The tumor could continue to grow slightly six to twelve months after surgery through this 'parallel' treatment in our clinical observations. It would eventually stop the growth and even gradually dissipate. A relatively small number of patients will need a second tumor removal surgery because of persistent symptoms.

It’s also important to note that currently, one important drug could likely be the key for future giant cell tumor of tendon sheath (pigmented villonodular synovitis) treatment. That is, Pexidartinib (PLX3397), a CSF-1 receptor inhibitor. We were thrilled when we see the results of the use of PLX3397 to treat pigmented villonodular synovitis published in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) (**) and the Lancet Oncology (***) in 2015 by foreign medical teams! Currently (2017.4.3), Taiwan has not yet introduced this drug, but we hope by the end of 2017 we can see the introduction of this drug, which I believe many patients in need can be helped!

* Simultaneous Anterior and Posterior Synovectomies for Treating Diffuse Pigmented Villonodular Synovitis. Clin Orthop Relat Res (2012) 470:1755–1762

** Cryosurgery as Additional Treatment in Tenosynovial Giant Cell Tumors. Sarcoma Volume 2016, pp1-6

*** Structure-Guided Blockade of CSF1R Kinase in Tenosynovial Giant-Cell Tumor. N Engl J Med 2015;373:428-37.

****CSF1R inhibition with emactuzumab in locally advanced diffuse-type tenosynovial giant cell tumours of the soft tissue: a dose-escalation and dose-expansion phase 1 study. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16: 949–56

Surgical treatment for giant cell tumor of tendon sheath (pigmented villonodular synovitis) is not difficult, but post-surgical rehabilitation is very important! In addition, because of the higher recurrence rate, a low dose of radiation therapy is required. We look forward to more evidence to support the effects of the drug PLX3397 in the future. If successful, perhaps surgery will be no longer needed for GCTTS treatment!